Highlighted Paper: Association of Sedation, Coma, and In-Hospital Mortality in Mechanically Ventilated Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019–Related Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Retrospective Cohort Study

As we all realize and experience critical care is a complex and challenging balancing act of competing interests, and sedation and patient synchrony on mechanical ventilation to prevent lung damage is an excellent example especially in the unique COVID-19 world. In order for us to employ ARDSnet lung protective strategies and/or incorporate new strategies like driving pressures into our management, many patients will display ventilator asynchrony and require sedation, and possibly paralysis.

This said, we have known prior to COVID-19 that excessive sedation in the ICU is associated with worse outcomes1. Over the last two decades, even prior to COVID-19, sedation practices in the ICU have shifted drastically as a mounting body of evidence emerged supporting the use of lighter sedation with daily interruption and nursing-driven scale-based protocols like the “ABCDE Bundle” encouraging us to avoid deep sedation23.

It is imperative we apply the scientific principles of lung protective strategies, particularly in COVID-19 patients since they are at risk of self-induced lung injury (SILI) as a result of ventilator asynchrony4. In fact, we know that the incidence of pneumomediastinum in COVID-19 is associated with an almost 90% mortality, which underscores the need for strict lung protective strategies56. This is especially concerning because data from several studies suggest a relatively prolonged duration of mechanical ventilation in the COVID-19 patient population7. For example, a review of patients from Wuhan, China indicated that, of 37 subjects with ARDS, 20 were alive at day 28 and required some form of ventilatory support8.

However, the highlighted paper here has brought to light a very significant consequence of the deep sedation (RASS neg 3 or more) often utilized to overcome this challenge, and highlighted the enigma of management between the two criteria of ventilator asynchrony versus deep sedation that each needs to be avoided; but how?

Perhaps there is something unique with the hypoxia that is seen with COVID-19. The reality is that in my going on 22-year career in medicine I have never seen a patient with a P/F ratio of 60 looking at me and speaking to me (on high-flow nasal canula) relatively asymptomatic. COVID-19 brought me this experience for the first time, and it has been termed by many as the “happy hypoxemic”, where we see preserved oxygen saturation despite low partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood samples9.

This phenomenon is thought to occur because of:

- A leftward shift of the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve induced by hypoxemia-driven hyperventilation as well as possible direct viral interactions with hemoglobin

- Ventilation-perfusion mismatch ranging from “physiological shunts” from alveolar dead space ventilation from microthrombi or pulmonary embolus and/or alveolar overdistension in patients with compliant lungs10

In recognition of this unique pathophysiology some have suggested calling this entity Acute Vascular Disease (AVDS) instead of ARDS11.

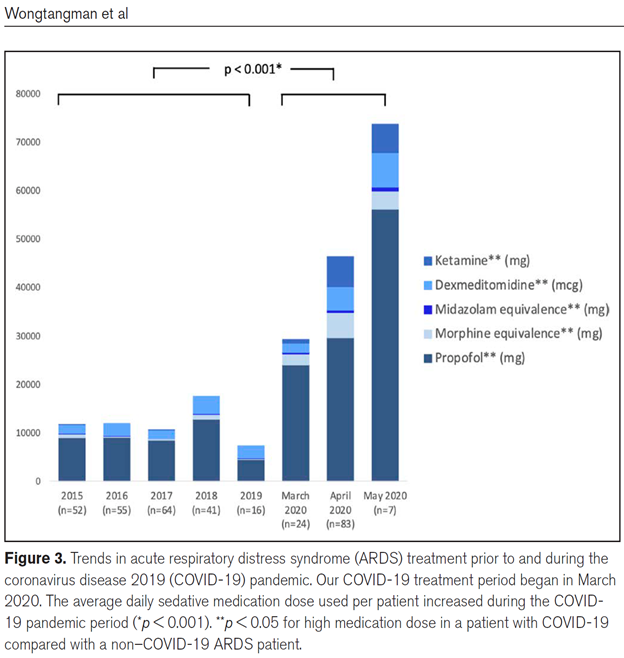

Given this unique and unprecedented respiratory pathophysiology at play in COVID-19, Wongtangman and colleagues documented that they had to induce coma (RASS negative 3 or greater) to achieve their mechanical ventilation goals. The chart below illustrates just how much sedation and various sedatives were utilized in their patients, as compared to prior years before COVID-19, that the authors required to achieve lung protective strategies.

The clinical dilemma with this management style is that the consequences of such high levels of sedation are that it is associated with an almost 6-fold increase in mortality.

To combat this some ICUs have resorted to prolonged paralysis to prevent VILI (Ventilator Induced Lung Injury), perhaps up to a week or longer as compared to the recommended 24 to 48 hours in the ARDSnet protocol. While no studies have been published specifically on this exact topic in COVID-19 patients of the consequences of excessive paralysis, in our opinion just as it was known prior to COVID-19 that excess sedation was associated with worse outcomes, the same is inevitably true in this patient population with excessive paralysis12.

Unfortunately, where we are left is in search of the “Holy Grail” in sedation with COVID ARDS practices focusing on safely minimizing analgesic and sedative doses and duration of administration13.

Since this often presents a conundrum, perhaps we need to change our thoughts and ideas about COVID related ARDS as Gattinoni and Marini are suggesting, and this might mean a migration away from conventional ARDSnet strategies. By now, for those of us on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic, we think that most of us have experienced that the COVID LUNG is very different from the ARDS lung from pneumonia, sepsis, etc. In those traditional ARDS lung clinical pictures the lung is laden with capillary leak and edema with high protein and atelectasis that requires HIGH PEEP and recruitment maneuvers – which in the COVID-19 lung may be more injurious. Recognition of this has been raised in Gattinoni and Marini’s commentary paper “Isn’t it time to abandon ARDS? The COVID‑19 lesson.”1415 To this end we provide guidance as to the COVID-19 respiratory failure unique ventilator management strategy we currently show favor to based on the paper by Gattinoni “COVID-19 pneumonia: ARDS or not?16” which is reviewed separately.

Another thought, and the authors note that it is only that at this time as formal research is needed in this area, is possible early tracheostomy in patients that are deemed likely to require prolonged mechanical ventilation in COVID-19. The theoretical rationale for this is that placement of a tracheostomy tube in patients with prolonged respiratory failure has shown advantages such as reduced work of breathing, improved secretion management, patient comfort, enhanced communication, and reduced need for sedation and paralytics, with the latter 2 aspects linked to serious long-term weakness and delirium17181920.

Should you have thoughts, comments, or experiences to share on this topic, please leave them in the comments section.

KEY TAKE AWAY POINTS

1. Covid ventilator sedation management is challenging because they are YOUNG, strong, and driven by respiratory ALKALOSIS and risk SILI.

2. COVID ARDS may be more of a vascular/inflammatory illness with compliant alveoli than traditional ARDS

3. COVID ARDS patients often require large amounts of sedation and NMB for ventilatory asynchrony for prolonged periods, but this may increase their mortality 6 FOLD…….is the CURE worse than the disease?

4. We should not abandon the ABCDE bundle and light sedation strategy, but in doing so this might require a change in our approach away from the traditional the ARDSnet strategy

5. Earlier tracheostomy may reduce patient discomfort/agitation, and perhaps could offer an answer for some patients

Authors:

Christopher Voscopoulos, MD, MBA, MS, MLS, FCCP, RPNI

President, Medical Specialists Associates

Board Certified in Anesthesiology, Critical Care, Pain Medicine, Addiction Medicine, Critical Care Echocardiography, Transesophageal Echocardiography, and Board Eligible in Neurocritical Care and Obesity Medicine

Nazir Habib, MD

Partner, Medical Specialists Associates

Board Certified in Internal Medicine and Critical Care

References:

-

- Pearson and Patel, “Evolving Targets for Sedation during Mechanical Ventilation.”

- Pearson and Patel.

- “Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) Center.”

- Weaver et al., “High Risk of Patient Self-Inflicted Lung Injury in COVID-19 with Frequently Encountered Spontaneous Breathing Patterns: A Computational Modelling Study.”

- Tacconi et al., “Incidence of Pneumomediastinum in COVID-19: A Single-Center Comparison between 1st and 2nd Wave.”

- Tonelli et al., “Spontaneous Breathing and Evolving Phenotypes of Lung Damage in Patients with COVID-19: Review of Current Evidence and Forecast of a New Scenario.”

- Divo et al., “Methods for a Seamless Transition From Tracheostomy to Spontaneous Breathing in Patients With COVID-19.”

- Yang et al., “Clinical Course and Outcomes of Critically Ill Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A Single-Centered, Retrospective, Observational Study.”

- Dhont et al., “The Pathophysiology of ‘happy’ Hypoxemia in COVID-19.,” 19.

- Dhont et al., “The Pathophysiology of ‘happy’ Hypoxemia in COVID-19.”

- Gattinoni and Marini, “Isn’t It Time to Abandon ARDS? The COVID-19 Lesson.”; Gattinoni, Chiumello, and Rossi, “COVID-19 Pneumonia: ARDS or Not?”

- Segredo et al., “Persistent Paralysis in Critically Ill Patients after Long-Term Administration of Vecuronium.”

- Wongtangman et al., “Association of Sedation, Coma, and In-Hospital Mortality in Mechanically Ventilated Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019-Related Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Retrospective Cohort Study.”

- Gattinoni and Marini, “Isn’t It Time to Abandon ARDS? The COVID-19 Lesson.”

- Attaway et al., “Severe Covid-19 Pneumonia: Pathogenesis and Clinical Management.”

- Gattinoni, Chiumello, and Rossi, “COVID-19 Pneumonia: ARDS or Not?”

- Divo et al., “Methods for a Seamless Transition From Tracheostomy to Spontaneous Breathing in Patients With COVID-19.”

- Diehl et al., “Changes in the Work of Breathing Induced by Tracheotomy in Ventilator-Dependent Patients.”

- Epstein, “Late Complications of Tracheostomy.”

- Shehabi et al., “Early Intensive Care Sedation Predicts Long-Term Mortality in Ventilated Critically Ill Patients.”